Choi Tae-young, an indelible sound memory: from visionary technique to human philosophy.

- Elisa Nori

- Sep 25, 2025

- 53 min read

Updated: Sep 27, 2025

When it comes to coloring through a sound project, we know that everything depends on the message we want to convey, the purpose we establish, be it artistic, functional, or communicative.

The art of creating, shaping, and processing sound elements for different multimedia contexts is the spirit of sound design, allowing us to immerse ourselves in a language invisible to the eye but evocative to our hearing and sensitivity.

The advancement of three-dimensional sound, combined with the transition from analog to digital film, has become essential to providing the viewer with a fully immersive visual experience.

The counterpart of the visual element, sound design is the secret code we are called upon to decipher, to reveal to access what I would call a sensorial short circuit; in the world of cinema, rhythm and atmosphere immerse us in a sonic universe that amplifies our emotions in a harmonious fusion of images, music, sounds, the narrator's voice, and noises.

The viewing experience wouldn't be the same without a sound narrative that conveys the director's intentions, either coherently or in a completely revolutionary, often even contradictory, way: this depends on the result he wants to achieve for the audience.

We know that humans love what comforts, calms, and instils security, but anything disharmonious can immediately arouse discomfort, frustration, and agitation.

And it is precisely through sound design that we add or subtract, adjust intensity, and modulate so that the path we travel is friendly, familiar, or, conversely, unpredictable, tortuous, or even downright fatal.

The beauty of cinema is that we can go from a well-trodden path to a dirt road in a very short time, but it is this emotional ups and downs that keeps us glued to our seats, and no visual experience can be adequately savored without the skillful use of sound, a fundamental part of the plot's development, adding additional layers of depth and complexity to each scene.

If we want to talk about someone who manages, through his work, to stir viewers into a whirlwind of different perceptions, it's impossible not to mention sound designer

Choi Tae-young, also known as Ralph.

A prominent South Korean figure, he has demonstrated a mastery of this art, combining creativity and ingenuity, earning him a respectable international reputation and proving the excellence of Korean talent.

His high level of training and experience have allowed Ralph Tae-young Choi to work alongside award-winning directors, whose authority and esteem are recognized by a devoted audience.

Ralph's task is to communicate through the most hidden channels, caring for the director's vision and preserving its authenticity; you understand that a relationship of mutual respect and trust is essential.

Only in this way can we understand the immense work of a sound designer, who infuses his signature into every scene.

We know that the sound of a film is based on three fundamental elements: dialogue (Dialogue, DX), music (Music, MX), and sound effects (SFX).

Sound effects encompass various categories, including special effects (EFX), ambient sounds (BG), and sounds manually created in the studio using Foley, such as footsteps or object movements.

The undisputed protagonist is the screenplay, which dictates the pace and intention, expertly supported by a sound design that transforms it from paper into a three-dimensional narrative fabric.

Ralph Tae-young Choi's professional harmony with director Bong Joon-ho is well-known, having overseen the sound design for each of his projects, including the masterpiece Parasite, which won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Ralph Tae-young Choi spent a total of twelve weeks on Parasite: eight weeks on editing and audio recording, two on the pre-mix in Dolby Atmos, and another two on the final mix, which he did with director Bong Joon-ho.

The sonic contrasts created by the Live Tone Team artfully portrayed the wealthy Park family and the working-class Kim family, playing a decisive role in interpreting two worlds destined first to meet and then collide.

The Parks' large, spacious and quiet home contrasts with the Kims' cramped and sometimes claustrophobic basement: while in the villa, outside noises are almost inaudible, in the basement, every sound invades the space, amplifying the sense of oppression.

The difference is further accentuated by the location of the Kims' home: below street level, where sewage and dirt become true amplifiers of inequality.

The secret bunker closes the circle, representing the lowest level of desperation, escape, and the search for protection. In the film, the former housekeeper—formerly in the service of the villa's previous owner and architect—clearly specifies its use: in the event of an attack or break-in.

A slow descent into multiple levels, a stratification of society and its dichotomy.

Through his films, Bong Joon-ho honors what was once perfectly depicted by Italian neorealism: class struggle, social divide, and the resulting hardship. And this is what makes them incredibly intense.

In truth, these are perennially relevant themes, given that our planet does not recognize

a balance and a fair distribution of its resources for all... but they cannot be addressed in the same way; the approach adopted by South Koreans is, in my opinion, visual poetry.

Evils that seem ineradicable, yet find a light of relief in characters who still believe in something—just as happens in everyday life.

The grotesque dances with social injustice, just as the ideal of the struggle for life does with courage.

The ability of South Korean cinema to emotionally engage is evident and undeniable.

This is rooted in the collective memory and history of the people—from Japanese colonization to the occupation during the Korean War—but with the desire to share their own vision and life experience.

This historical journey is reflected in the country's creative repertoire, as well as in the impeccable balance of its works.

With the Live Tone studio, co-founded by Ralph Tae-young Choi in 1997, South Korea

is equipped not only with one of the best audio post-production facilities with cutting-edge technology, but also has the tools to foster audiovisual evolution by training new professionals and making a decisive contribution to cultural and industrial growth.

The team stands out for its ability to transform sound into an immersive experience that remains faithful to the directors' artistic vision.

Services Offered:

– Dolby Atmos (D-Cinema) Mixing

– 7.1/5.1 Channel Surround Mixing

– ADR and Voice Recording and Editing

– Sound Design and Editing

– Foley Recording and Editing

– Custom SFX Location Sound Recording

– Sound for HDTV, IPTV, Animation, Video Games, Multimedia, VR

Live Tone has achieved significant firsts in Korean cinema history, including the country's first 5.1-channel Dolby Digital audio production and the world's first 14.2-channel D-Cinema 3D audio production for the film The Yellow Sea.

From creating complex atmospheres and sound design, to mixing, ADR and Foley work, on-set sound effects recording, and post-production for animation, video games, virtual reality, and HDTV and IPTV content, the studio covers the entire spectrum of audio production, combining technical innovation and artistic sensibility.

Under the leadership of Ralph Tae-young Choi, the team has curated over 350 films and television series, a milestone that testifies to the studio's strength and impact in the industry.

Live Tone Studio has worked in a wide variety of genres, including highly successful television productions such as Squid Game, a prime example of its ability to combine creativity and technical rigor.

The use of traditional Korean sounds, integrated into the music and effects, undoubtedly helps to situate the series within its cultural horizon.

The work on this television series stands out for its skillful use of the contrast between silence and chaos, which amplifies the themes of lost innocence and the brutality of survival.

Everything typically associated with childhood and play, with the right use of sound, becomes a sinister and disturbing experience, contributing to the viewer's emotional trauma.

The tension and inhumanity are paradoxically always accompanied by a colorful and playful tone, which sends the audience into a tailspin, forcing them to oscillate between recognizing the typical figures of a joyful childhood as harmless or threatening.

Sound design requires not only paying attention to detail, but also observing the changes in circumstances and, with them, those affected by them.

An example of maximum tension and pressure masterfully conveyed through sound design is found in the first season's crossing of the Glass Stepping Stones; just as the choice of which slab to land on alternates, so do the emotions of the audience, left suspended like the bridge, amidst breathing, trembling, religious delirium, and the lack of clarity of the majority of the players.

They struggle between fear and the absolute necessity of logic and extreme concentration.

The slipping of shoes, the impact of feet on tempered glass supporting trembling bodies, and every time a death occurs, the glass pawns of the VIPs also mark their departure; a sound that echoes the macabre coldness.

The strategic use of silence allows viewers to focus on the characters' reactions and heightens the sense of isolation within the game, often dampened by confused incitements or, conversely, threats and coercion.

Dialogues are essential in this case because they reveal and prepare for the nature of individuals, especially in a game that sees them leading the way for those waiting behind them.

An example of active and guided listening occurs when one of the contestants, a glass expert, reveals that tempered glass produces a different sound than ordinary glass: the sound becomes, at that moment, a mirage of orientation and a means of salvation.

In this case, the sound design not only accompanies the action but also becomes a narrative language, forcing the viewer to share the tension of listening.

The climax is reached with the consecutive explosion of the remaining glass pieces at the end of the game, making each break feel like a sharp, rhythmic shot, almost like the sound of a machine gun, until it reaches the protagonists, with a masterful use of slow motion that amplifies the impact of the glass shards and intensifies the experience of the scene.

In the second season, the enormous platform of the game, The Gathering, also known as Mingle, which simulates a gigantic carousel, alternates between passive and active phases: the first is filled with tension and anticipation, devoid of dialogue and drowned out by the music accompanying the carousel's rotations; the second is dominated by the chaos of the players, their agitated and anguished dialogues, and the ticking of time.

All this takes place in a dual light atmosphere that shifts between colors and stability, amplifying the panic.

When the music stops, claiming a free room with the exact designated number becomes a real struggle, but also the only chance of survival.

Brutal elimination is the inevitable consequence for those players who fail to find a team or a room.

The sound of the locks locking and unlocking is the undisputed protagonist, along with the time limit, while the mechanical sounds of the carousel—metal creaking, rotation, and vibrations—convey the physicality and weight of the structure; they give the scene grandeur by overwhelming the human presence and engulfing the spectators.

The echoing structure thus makes the situation even more ominous.

Sound design is not only essential to fully experiencing a film, but when masterfully executed, it surpasses our intuition and expectations.

The path, which has made this discipline a piece of an otherwise incomplete puzzle, demonstrates a fundamental stage that played a key role in shaping the field we know today.

The term sound design originated in the mid-1970s.

Films like Apocalypse Now and Star Wars truly defined the role of the sound designer, marking a new milestone in the evolution of cinema.

Walter Murch and Ben Burtt emerged as key figures through the legacy they helped create: Murch, working on Apocalypse Now, studied and decomposed helicopter sounds into individual components to synthesize them, so that the soundscape was realistic and adaptable, and every detail contributed to building tension and atmosphere; the latter created a library that over the years came to contain more than 5,000 sounds, used for the iconic sound effects of Star Wars and other films such as Indiana Jones, E.T., Wall-E and Alien.

Burtt’s gift was not only to perform the technical procedures necessary to record and then manipulate sounds coherently with images, but also to intuit and select the most suitable sonic reality for each character, place, action, circumstance, and emotional situation.

All this is demonstrated through the Star Wars saga, whose success is undeniably linked to sounds, each animated by an unmistakable identity, almost as if they possessed a life of their own.

Just think of the lightsabers, the noises made by the small robot R2-D2, the voice and unmistakable breathing of Darth Vader, the voice of the Wookiees (Chewbacca), the laser pistols, the droid C-3PO, the buzzing TIE Fighters, the rumble of the Millennium Falcon, and even the ambient sounds of planets, like the wind of Tatooine or the creaking ice of Hoth.

The verisimilitude of the cinematic world was not only consolidated in this way, but evoked indelible impressions, confirming that sound design plays a central narrative role and goes far beyond its technical function.

Furthermore, footsteps, movements, and objects found a new dimension with the art of Foley: the studio reproduction of essential sounds that gave the film greater coherence and intensity, becoming a fundamental element destined to influence sound design for decades to come.

This sonic dimension, which I would define as poetic, to the extent that it is capable of orienting the listener's mood and reactivity, has much older origins than those generally known, even though they are not always adequately documented or fully substantiated.

Even in prehistoric times, sound was not just an echo of nature, but a bridge to the supernatural: it stimulated emotions, emphasized actions, anticipating a design-led use of the soundscape.

In ancient Egypt, temples and tombs were designed to transform voices, songs, and drums into reverberations and amplifications: a true "designed acoustic".

Even the ritual silence was not accidental: as in modern sound design, it served to create tension and contrast with sudden, echoing sounds. Corridors, columns, and openings produced the effect of sound movement, a primitive directionality similar to that used today in films, video games, and installations.

Examples of layering appear in Egyptian rituals: drums, percussion, chants, and natural sounds intertwined in complex textures, anticipating modern techniques of sound depth.

In Greek theater, the deus ex machina was accompanied by the thunder of percussion;

in India, the Natya Shastra codified the use of music and rhythms as a narrative language.

The Greeks and Romans built mechanical stage devices in theaters capable of simulating the sounds of everyday life, and masks amplified voices—true prototypes of voice shaping.

The Hydraulis, a water organ, transformed air and pressure into liquid, vibrant timbres: an embryonic form of mechanical sound design.

In imperial China, stairways, corridors, and pavilions were designed to resonate with every step: architecture that became sound instruments, anticipating concepts of spatial audio and even sound branding.

On the Korean peninsula, instruments such as gayageum, geomungo, large drums and bronze bells created ritual soundscapes, transforming space into a sounding board of the sacred.

Among the Maya and Aztecs, zoomorphic shells and whistles were not simple instruments, but keys to the invisible world. The blowing of shells could transform into wind or thunder, while whistles emitted animalistic cries or ghostly screams. Death whistles were famous, capable of releasing high-pitched, piercing sounds that, even today, science recognizes as disturbing to the human brain: primordial echoes that reverberate like voices or screams, designed to instill fear and awe in sacred rituals.

During the Renaissance, theaters used automatons to simulate thunder, birds, and waves; Leonardo da Vinci designed "optical-acoustic" devices and studied reflection and propagation, anticipating modern concepts of reverberation and spatial audio.

With Futurism, sound established itself as an autonomous art. Luigi Russolo denounced the predominance of pure sounds and transformed noise into music. His Intonarumori recreated the roars of engines, airplanes, thunder, machines, and crowds: the first embryonic forms of Noise Music.

The instruments were classified into families (cracklers, gurgling, rumbling, buzzing, popping, hissing, creaking, howling), each divided into registers (soprano, alto, tenor, bass): a systematic catalog of noises that ushered in a new acoustic dramaturgy.

Do you still believe that sound has no crucial value and weight, or are you aware that everything we hear, directly or indirectly, influences us emotionally, psychologically, and structurally to the point of benefiting or, conversely, even harming us? This is not a simple archive of historical curiosities: it is the essential premise for understanding how sound became a universal language.

With this enormous power in mind, we delve into the space and sonic dimension of a sound designer who continues to amaze and create a vibrant world with passion and dedication.

While sound design was already establishing itself as an independent profession in the West in the 1970s, in Korea, cinema was undergoing a transformation in the 1980s and 1990s: the technological revolution, along with progressive cultural openness and new infrastructure, laid the foundations for South Korea's international prominence in the decades to come.

The Busan International Film Festival, founded in 1996, fostered this vision, representing a symbolic turning point.

A new generation of directors and technicians began to be trained thanks to the Korean Academy of Film Arts, founded in 1984, while the Korean Film Council urged industry renewal, and liberalization allowed large private companies like CJ Entertainment and Showbox to invest in technology and professionalism.

The state shifted from censorship to active support, establishing laws, funding, and incentives for film, television, music, and video games.

Subsequently, the Korean Wave would establish South Korea as a media powerhouse with a strong identity, amplifying global demand for content and imposing not only higher visual standards but also a growing focus on sound quality.

It is within this historical and cultural context of openness and renewal that Ralph Tae-young Choi's career developed, as he helped redefine the sound language of Korean cinema, bringing the skills he acquired in Los Angeles to his home country.

From 1998 to the present, Ralph Tae-young Choi has received numerous awards at major Korean festivals, including the Grand Bell Awards, the Chunsa Film Awards, the Korea Film Awards, and the Asia Pacific Film Festival, as well as international prizes such as the MPSE Golden Reel Award in the United States.

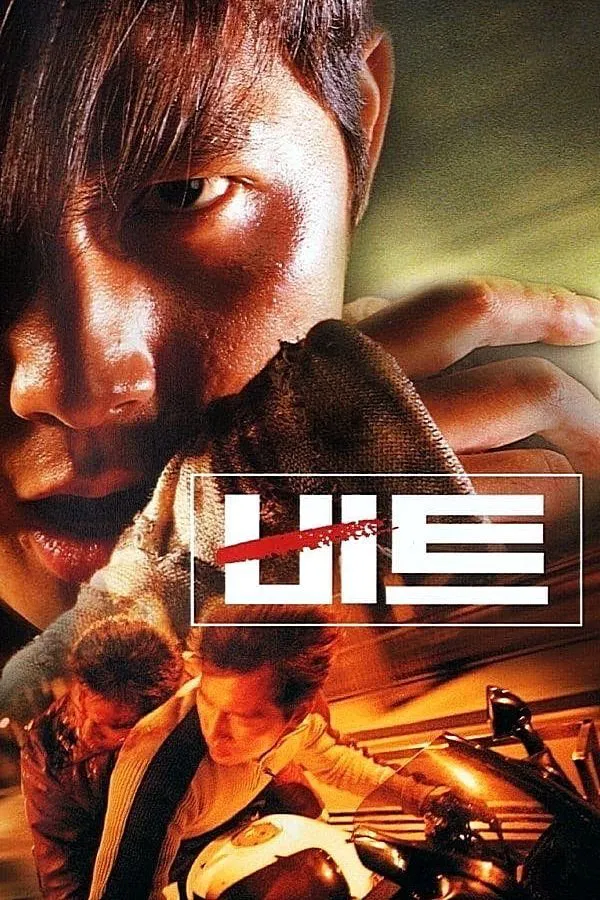

Among the titles that have marked his career are Beat, The Foul King and Volcano High, followed by Save the Green Planet! and A Tale of Two Sisters.

With The Host, he achieved a double triumph, in Korea and at the Asia Pacific Film Festival, consolidating his fame with works such as The Good, the Bad, the Weird, War of the Arrows, Roaring Currents, The Throne and The Fortress.

Global recognition came with Parasite, which won the Golden Reel Award, and was renewed more recently with Exhuma, winner of the Baeksang Arts Awards.

We enter a sonic narrative that will lead you not only to a deeper embrace of sound awareness, but also to internalize the possibility of being a visionary through its use. In the vivid memory of our lives, we want to carry with us not only beautiful images, but the full range of what our hearing has been capable of capturing. The cinematic sound experience aims to remind you of those everyday emotions in different forms and possibilities, but never with less intensity.

Ralph Tae-young Choi's words will resonate with you for a long time, leaving you with the essence of his invaluable experience.

1. After studying sound engineering at the Los Angeles Recording School,

as well as music business and sound engineering courses at UCLA Extension, you returned to Korea and founded Live Tone, entering an industry undergoing rapid transformation in the 1990s—an undoubtedly dynamic period.

What drove your decision to pursue a career in film audio post-production?

The transition from analog to digital in those years was crucial, as was the emergence of Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs), VST plug-ins, surround formats like Dolby Digital and DTS, sampling tools and software synthesizers that revolutionized the way sound is created and manipulated.

How did you experience these innovations? How did they shape and influence your vision, as well as your work in audio post-production?

Ralph T.Y.C - After completing my audio studies in Los Angeles, I began my career as a sound engineer in Korea as one of the founding members of Live Tone Studio. Prior to studying abroad, I had been active in the Korean popular music scene, where I met the future founder of Live Tone, who was then working as our team’s sound engineer.

After returning to Korea, I joined him in founding Live Tone in 1997.

At that time, Korean films were still produced in analog Dolby Stereo SR format for theatrical release, and the industry was in transition from analog to digital recording systems. In its early days, Live Tone handled both music recording and audio post-production for film services, but after 2000, it became a studio dedicated exclusively to audio post-production for film and video.

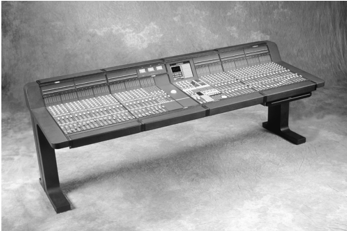

In the early years, I worked with the Euphonix CS3000 mixing console, a hybrid console that combined digital mixing processes with analog input and output. For multitrack digital recording, I operated six SONY PCM 800 recorders - five were used as 40-channel playback machines, and one was used as a dubbing recorder for 5.1 channel and LtRt print master recordings. I also utilized Pro Tools (V5) for editing music and other sound elements.

Our first project, Beat (1997), was mixed in analog Dolby Stereo, while the third project, Deep Sorrow (1997), marked Korea’s first theatrical Dolby Digital 5.1 channel mix. For this project, I invited a Hollywood mixing engineer to collaborate on the final mix, which became the starting point of my ongoing collaborations with the Hollywood sound crew and systems. Over time, I adapted their workflows to the Korean context, helping to establish standardized crew structures and audio post-production processes.

I focused on learning and introducing new cinema audio technologies, producing Korea’s first theatrical Dolby Digital 5.1ch (Deep Sorrow, 1997), Dolby Digital SurroundEX 6.1ch (Volcano High, 2001), Dolby Digital 7.1ch (War of the Arrows, 2011), and Dolby Atmos (Mr. Go, 2013). In 2011, I also co-developed CJ CGV’s 14.2 channel theatrical system and participated as an early developer of Korea’s immersive sound format, STA (Sonic Tier Audio).

Currently, I work in a certified Dolby Atmos mixing stage equipped with an AMS NEVE - DFC audio console, two Pro Tools systems for playback (384ch I/O), and one Pro Tools system to recording (192ch I/O) for print master and audio stems.

These technological innovations have contributed significantly to the advancement of Korean film sound, while also inspiring directors with new creative approaches to audio storytelling.

As a result, I won the MPSE Golden Reel Award in the Foreign Language Sound Editing for Parasite, and in the same year, I became a member of the Oscar Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Sound Branch in the USA.

2. You and your team oversaw the entire soundtrack for the globally successful television series Squid Game, from the first season to the last, blending artistic vision and technical expertise; a soundscape that is both authentic and indelible.

I would like to focus in particular on the third season, released in June of this year and eagerly awaited.

The extraordinary success achieved—not only in terms of viewership and positioning in various countries, but also in cultural impact—has pushed Netflix to significantly increase its investment in Korean content, resulting in a higher percentage of global subscribers interested in South Korean productions.

The series' conclusion is certainly, also due to scripted necessity, the height of tension and violence, albeit with an emblematic finale.

The progressive loss of crucial figures, to whom we become attached through empathy, increases the psychological pressure on the viewer.

The pace becomes pressing and oppressive with the game Hide and Seek, which opens the season in a decisive and disturbing way.

It serves as a prelude to what is, in my opinion, perhaps the most brutal and direct game among the players.

The weapons used, daggers, require close physical contact; but above all, the dynamics and choices to be made bring out the participants’ true nature or cause them to lose themselves under the pressure of the game.

The sound of doors opening and closing, keys in locks, the beat that marks time, as well as moments of panic, the stabs of knives, the scuffles, the footsteps and runs that accompany the desperate search for the right direction to the exit; all elements that define the sound design, whose purpose is to convey the urgency, inhumanity, and precariousness of the situation.

Finally, the Squid Game in the Air : an echoing and imposing space, completely opposite to the opening one. The surface on which the few remaining players move, however, is limited, with the obvious disadvantage of height.

On the other side, protected in a seemingly inaccessible environment, the VIPs scrutinize and discuss the participants' choices and moves.

Here, the sound design follows the unstable strategic dynamics of those who want to advance through the rounds without falling into the void, with flimsy pacts and promises.

Group violence resurfaces, with brute force exerted on the weakest; there is no room for unanimity, but rather an overpowering need to dominate.

It all ends with a symbolic sacrifice, decisive in saving a new life.

What was it like working on a project capable of shaping the contemporary cultural scene, where sound design leads millions of viewers into a remarkable emotional vortex?

In the final mixing phase, what were the most complex aspects to manage in order to achieve uniformity in the soundscape without losing the rawness of the most violent scenes?

Is there a sequence from the third season in which sound played a decisive role in guiding the viewer's reaction and that you recall as a particular challenge?

Ralph T.Y.C - My first collaboration with director Hwang Dong-hyuk was on the film Miss Granny. Later, while working together on The Fortress, I came to realize how remarkably skilled he is at capturing and portraying the subtle emotional shifts of characters in relation to their circumstances and surroundings.

In the Squid Game series, Hwang once again depicted with intensity how the good and evil within human nature constantly shift depending on environment and situation.

The participants, forced to kill or be killed in a relentless cycle of survival games, are driven to moments of agonizing choice. Audiences projected their own real-life experiences and emotions onto these characters, feeling empathy and outrage, and ultimately consuming the drama through their own selective emotions. This resonance allowed the series to capture the hearts of global viewers, writing a new chapter in television history.

The games featured in the show were all traditional pastimes familiar to Koreans, and I myself grew up playing them as a child. Looking back, I realize that these games taught me about competitiveness and the necessity of moral judgment and proper decision-making to achieve victory. In many ways, they served as a rehearsal for entering the highly competitive Korean society as an adult.

From a sound design perspective, Squid Game posed significant challenges.

To convey the extreme situations and emotions of the characters, I designed diegetic sound effects that alternated between intense, terrifying, and exhilarating.

These sounds functioned as a psychological layer, expressing the characters’ states of mind and decision-making processes. At the same time, violent and brutal sound effects were deliberately employed to immerse the audience in the characters’ direst moments of survival. Complementing this, composer Jung Jae-il’s non-diegetic score was interwoven with the sound effects, amplifying the director’s creative intent.

Yet there were also inherent technical limitations within the OTT platform environment. Unlike theatrical films, it is difficult to achieve the same dynamic range of sound.

Moreover, global OTT services mandate strict loudness standards, which required me to deliver mixes more centered on dialogue, inevitably reducing the richness and dynamics possible in a theatrical format. The diverse home viewing setups - smart TVs, soundbars, and personal devices - made standardization impossible, limiting the cinematic experience.

In fact, many audiences consumed the show with subtitles, relying more on reading than on listening, which meant the director’s precise sonic vision was not always fully delivered.

This limitation ironically reaffirmed the enduring value of cinema. For example, Netflix’s animated film

K-Pop Demon Hunters was later expanded into theatrical screenings, where audiences rediscovered the irreplaceable cinematic experience - large screen visuals, dynamic sound, and the collective energy of a crowd – that OTT could never replicate.

The final game, The Squid Game in the Air, represented the ultimate sound design climax of the series. In this sequence, every breath, line of dialogue, piece of score, and sound effect was focused on being as primal and instinctive as possible. It conveyed the extremes of human nature—from ultimate goodness to the depths of evil, even embodying parental sacrifice. My aim was for audiences to confront the question directly: “If I were in this situation, what choice would I make?” Designing the sound to provoke this reflection was the ultimate goal.

3. Your long-standing collaboration with director Bong Joon-ho has revealed a journey of brilliant complicity and mutual respect. Together, you have succeeded, with different yet complementary approaches, in bringing to light the most intimate and complex dimensions of screenplays.

Both nationally and internationally, you have guided audiences toward a vision of cinema that combines intellectual rigor and emotion, a balance that is far from obvious in today's landscape.

Bong Joon-ho's ability to delve into the human soul is undeniable, revealing its dark and contradictory aspects as well as compassionate traits. This duality is expressed with extraordinary effectiveness, from family dynamics to major social struggles.

From his debut with Barking Dogs Never Bite, human duplicity emerges: it manifests itself in everyday dynamics and in all its facets, even the morally disturbing ones, to the detriment of defenseless animals.

With Memories of Murder, man's imperfect and brutal nature lashes out at his fellow humans, unleashing perversion and cruelty.

In The Host, an amphibious creature is born from carelessness and arrogance toward nature, demonstrating how irresponsible actions generate disastrous consequences that affect even the innocent.

In Mother, a young boy's mental disability and his mother's overprotectiveness become a seeming refuge from their marginalization, while those who should support them remain blind to their fragility and desperation.

With Snowpiercer, the train becomes a social allegory: the poor are relegated to the back carriages, the rich to the front. Inequality inevitably leads to conflicts and revolutions, while the failure of an experiment imposes discriminatory rules on the survivors.

Okja denounces consumerism and profit, portraying ruthless consumers incapable of recognizing animal suffering. False environmental promises mask a capitalism interested only in self-interest, while purity and salvation remain rare and pristine.

In Parasite, two economically opposed families demonstrate social stratification and how interactions are guided not only by verbal language, but also by opposing behaviors and goals.

Finally, Mickey 17 explores human greed in space: life, both that of others and our own, is expendable if it serves the interests of the majority, and nothing is indispensable if everything can be useful.

First of all, my compliments for your colossal contribution. I'm a fan of sound and music, and at the same time I recognize the utmost importance of the screenplay.

As I like to reiterate: a film with excellent sound and music, even if the visuals are not particularly strong, can still have an impact... while the opposite is completely impossible.

Of the entire soundscape created alongside this great director, what moments or technical choices do you remember as "special" for the final message?

For Mickey 17, released this year, you collaborated with award-winning sound designer Eilam Hoffman on the film's alien lifeforms, the Creepers; for the human printer featured in the work, you used the sounds of an old dot matrix printer and an inkjet printer.

What role, in your opinion, does the viewer's subconscious recognition of real sounds play in making non-existent creatures or technologies more believable?

How much do psychological and imagined "biological" dynamics intertwine in the sound design process?

Ralph T.Y.C - The opportunity to work on every film with Director Bong Joon-ho has been the greatest fortune and blessing of my life. With each addition to his filmography, I learned many of his sound-directing techniques, which became a driving force in advancing my own approach to sound in cinema. These methods were then applied and expanded to other Korean films as well.He has an exceptional ability to clearly define the ambiguous emotions embedded in characters and events, and to deliver them to the audience with tremendous power.That strength distinguishes his films as a unique genre apart from other media, and audiences watching his films in theaters fully absorb the clarity of the messages he intends to convey.As a sociology major, he also demonstrates a keen and vivid exploration of human nature through his films.

Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000)

Working on Director Bong’s debut feature Barking Dogs Never Bite was a very special experience.In one scene, a janitor secretly cooks food in the basement, is caught by the building superintendent, and the two end up sharing the meal while the janitor tells comic anecdotes about a boiler repairman named Mr. Kim. I witnessed Bong’s attention to detail in the way he synchronized the timing and pacing of the comic dialogue with various sound effects from the basement pipes overhead.

Another scene shows the heroine tying her yellow hoodie tightly and rushing to rescue a dog on the rooftop, while crowds in yellow raincoats scatter confetti from a water tank above—an image reminiscent of a comic book.The various ways people treat dogs in a single apartment complex highlighted the absurdity of modern Korean society and the relationships of the marginalized.

Bong staged these scenes with improvised jazz percussion, and I remember spending countless hours editing improvised jazz drum recordings to match the tempo of the cuts and scenes, at the director’s request.

Memories of Murder (2003)

In Memories of Murder, Bong sought to preserve the raw atmosphere of the production dialogue. During the ADR recording sessions, he had an on-set boom operator from the crew handle the microphone while actors re-recorded their lines.

The actors performed while watching the scenes, maintaining minimal movements as they had during filming, in order to retain authenticity. This became a unique recording method that reflected Bong’s meticulous approach to directing emotional dialogue delivery.

This technique reached its height in the film’s climactic sequence - at the rainy railway tracks, when the detective confronts the suspect, realizes he cannot be certain, and lets him go.

At that moment, Song Kang-ho delivers the line, “Have you been eating well?”, with a tone of bitter irony, and the emotional impact of the dialogue was pushed to its peak.

Because the original production sound was overwhelmed by rain noise, the entire sequence had to be re-recorded in ADR. Bong and I worked tirelessly to capture the realism and maximize the characters’ emotions, ultimately creating one of the most powerful soundscapes.

The Host (2006)

The Host was Director Bong’s first film featuring a creature. Before reading the script, I was excited, thinking I finally had the chance to create something akin to Hollywood’s Alien. However, once I read it, I realized this was not merely a creature film - it was a family story with a powerful social message.

To design the creature’s sound, I began with the base of a sea lion’s call, then layered in the sounds of pigs, monkeys, and other animals depending on the creature’s actions.

For moments where ordinary animal sounds could not suffice - such as the noise of the monster swallowing people and regurgitating undigested bones, or the sound of it snoring while asleep - actor Oh Dal-su performed the creature’s voice.

We recorded his performances and designed them into the monster’s final sound.

The climactic roar of the creature as it is struck by a flaming arrow carried special significance for Bong.

He wanted the roar to express not just pain, but a message: “You filthy humans! I, too, am a victim of your polluted wastewater. I am truly wronged.” The monster’s agonized cry, voiced by Oh Dal-su, conveyed this emotional depth.

Mother (2009)

Mother represented the pinnacle of Bong’s meticulous sound direction, and for me, it was a film of countless trials and errors as I strove to meet his exacting standards.

The film opens with the sound of a cleaver slicing through medicinal herbs while the mother watches her son play outside. This sound was designed to reflect her growing anxiety.

To achieve this, I recorded different kinds of dried herbs, capturing how the sound changed depending on their dryness, and matched it to her psychological shifts.

Other carefully crafted sounds included:

• The shocking impact sound when a stone thrown by the son strikes a girl in a dark alley.

• The shifting tone of rain sound as the mother carries a golf club (the murder weapon) to the police station.

• The heavy wrench sounds during the killing of the junk dealer.

• The rustling of reeds in the wind as the mother wanders after setting the junkyard ablaze.

All of these were based on realism, yet designed so as not to feel artificial or exaggerated, while still retaining cinematic strength and weight.

This approach clearly distinguished Bong’s sound direction from Hollywood styles.

His unique method ultimately paved the way for Parasite, where we achieved the most distinctive and authentically Korean form of K-Sound.

Snowpiercer (2013)

Snowpiercer required recording and building an extensive library of train sounds in order to design the film’s diverse soundscape. For this, I collaborated with Boom Library in Germany. They recorded trains across Europe and shared the material with me, later they are releasing it commercially as the Train library. Using this as a foundation, I designed the many train sounds featured in the film.

The train crossing at high speed in the opening, the train smashing through walls of ice - these needed to feel like the train itself was a living organism.

To achieve this, I layered and synthesized the roars of lions and tigers into the train sounds.

One of the most memorable challenges was the scene where the protagonist faces off against the guards just before battle, as the train crosses Yekaterina Bridge on New Year’s Day. For this, I recalled the heavy, resonant sound of a Korean high-speed train crossing the Noryangjin Bridge in Seoul, which I had once heard while biking along the Han River.

To recreate it, I placed microphones under the bridge and recorded the sound directly, later using it in the film.

The engine room was also designed according to Bong’s vision: it had to feel like an engine with an eternal, beating heart - never stopping, always alive.

The very last sound design to be completed was the crunch of footsteps in snow, when Yona steps onto the earth after the train’s derailment. I wanted it to capture the purity of freshly fallen, untouched snow. I waited for heavy snowfall, and finally, in February of that year, I went out at dawn to a park and recorded the sound of stepping into new snow.

That became the final sound in the film.

We mixed the film in 7.1 surround, expanding beyond 5.1 to deliver a richer, more immersive cinematic experience.

Okja (2017)

Okja was Korea’s first Netflix project, and Netflix’s very first Dolby Atmos home release.

It was also Bong’s second creature film, one layered with strong social messages.

Bong defined Okja as an introverted, timid female pig.

To capture this character, actress Lee Jung-eun - who later appeared as the housekeeper in Parasite - performed Okja’s voice, which was then incorporated into the sound design.

Additionally, sound designer Dave Whitehead from New Zealand, with whom I had collaborated on Snowpiercer, made recordings of Kunekune miniature pigs by himself, which were used in shaping Okja’s sounds.

For the truck sequences, I mounted microphones in multiple locations on the actual truck used in the film and recorded while driving. These recordings were applied to the scenes where Okja is transported in Korea, before arriving in the U.S.

Photo credits: Live Tone Studio

The scene I spent the most time mixing in Okja was the New York parade.

As Mi-ja and Lucy prepare their makeup and costumes for the event, the distant sound of the marching band gradually grows closer, building anticipation for the ceremony.

The sequence then flows seamlessly into the chaos of Okja’s escape from the stage—requiring extremely precise and complex sound detailing.

At the slaughterhouse, Mi-ja’s shock was expressed through rhythmic metallic machine sounds, and the sound of the killing gun was carefully designed to mirror her psychological trauma.

Originally, Okja was produced in 7.1 channel format for theatrical release.

Later, I created a separate near-field mix for Netflix. However, due to the technical limitations of OTT platforms, the cinematic dynamic range could not be fully conveyed.

This was a major disappointment for both Bong and me, and it reaffirmed our commitment to focusing more on cinema sound in subsequent projects.

Parasite (2019)

Parasite was another entirely new challenge. The film’s vertical spatial structure worked seamlessly with the Dolby Atmos format. Instead of employing Hollywood-style sound design, our goal was to base everything on real-life sounds, giving audiences a truly cinematic experience rooted in authenticity.

For dialogue, we emphasized differences in reverb of space to highlight the contrast between the rich and the poor. For sound effects, our aim was to recreate real sound, tangible sounds as vividly as possible.

Some of the Foley recordings I performed myself.

For instance, I contributed the sharp, powerful hand clap used in the scene where Ki-woo (the son) visits for his tutoring interview, and the housekeeper Moon-gwang claps loudly in the garden to wake up Mrs. Park.

In another humorous moment, Bong even inserted my name into the film: during the scene where the Kim family returns home in a torrential downpour, a neighbor shouts in the background, “Taeyoung! Taeyoung! Hurry, get out of the house!” It was a small but personal touch.

Other key sequences included:

• The montage of the Kim family infiltrating the Park household.

• The basement air-tone ambience.

• The overwhelming rainfall during the flood.

• Everyday background ambiences.

• The chaotic birthday party for Da-song.

All of these were orchestrated by Director Bong as if conducting a symphony, blending music, sound effects, and dialogue into a cohesive performance.

Parasite adhered strictly to a uniquely Korean sound-design philosophy, which ultimately became the benchmark for K-Sound. For me, it was the most meticulously mixed project of my entire career - and the one I am most proud to showcase.

Mickey 17 (2025)

Mickey 17 marked my first direct experience with the Hollywood production system, as I personally handled contracts, schedules, and negotiations.

At the outset, I wrestled with whether to adopt Hollywood-style sound direction or maintain Bong’s distinct style. The decision, in the end, was clear: Bong’s style would guide us.

Still, our first objective was to ensure that global, English-speaking audiences familiar with Hollywood sound grammar could enjoy the film without feeling alienated.

Thus, while the format of English dialogue and certain sound effects followed Hollywood conventions, the overall sound direction remained true to Bong’s philosophy. During pre-production, I created early designs for the “Creeper” creature sounds, which were later developed and completed by Eilam Hoffman in his own way.

In the mix sessions, we adhered to Bong’s K-Sound principles, integrating the musical score fluidly with sound design to ensure narrative impact. The final mix was unmistakably Bong’s style.

His signature approach involves bold omissions of sound, or conversely, obsessive layering of intricate details, sudden explosive climaxes, and, at times, the deliberate use of silence. These techniques were also evident in Parasite.

Although Bong’s sound philosophy may appear abstract, subjective, or even unfamiliar to Western audiences, it transcends formal style to touch universal human emotions in a direct and powerful way.

The film’s final sequence - Mickey’s nightmare - was crafted according to Bong’s sound grammar, meticulously designed and mixed. After reviewing the finished Dolby Atmos cinema version, Bong expressed immense satisfaction with the sound.

He even hinted at his next project, signaling that his cinematic train was already moving forward - one I was fortunate enough to board once again.

Whenever I work with director Bong Joon-ho, I follow one rule: make it sound real first and add imagination only when the emotion reaches its peak. Audiences unconsciously know the rules of everyday sound. So the more I present creatures or technologies that don’t exist in reality, the more I must first let them hear evidence of how those things touch this world.

To do that, I start with a higher proportion of realistic sound than style. I stack the layers in order: the foundational space (room tone and ambience), movement (footsteps, machines running), and on top of that the character’s signature sounds (dialogue, breathing, voice-over). When the drama peaks, I briefly allow bolder stylization and then return right away to the realistic layers. This way, the audience accepts it with their bodies before they analyze it with their minds.

I also shape psychology and the “biological feel” through sound. As tension rises, I make the sound a bit rougher and more irregular, gently lift a thread of high-frequency noise, and add a subtle low thump like a heartbeat. When empathy deepens, I stabilize the sound, nudge the pitch slightly downward, and lengthen the breath to give warmth. I control these shifts smoothly with automation on the mixing console.

In the end, my job is to precisely touch the everyday sonic memories the audience already carries, so that even things that don’t actually exist on screen feel real. Laying down the cues of reality first and raising the volume of imagination only when it’s truly needed—that is the basis of my sound direction.

4. Dexter Studios is a South Korean pioneer in post-production and content creation, specializing in VFX, Digital Intermediate, virtual production, and creative development.

The company integrates technological advances, advanced research, and artistic creativity to transform narrative visions into immersive, world-class visual experiences, working on films, TV series, animation, immersive media, and advertising campaigns.

Your collaboration includes films and series with incredible creative and commercial success, and your synergy has also borne deserved fruit in your working relationship with Netflix—for

Live Tone, which began with Okja— allowing your work to become increasingly popular abroad, and with it, Korean content.

From the recent Squid Game – Season 3, Omniscient Reader: The Prophecy, Harbin, Exhuma, Alienoid and Alienoid: Return to the Future, Moving, 12.12: The Day, Mask Girl, Black Knight, The Moon, Space Sweepers, Parasite, Along with the Gods – to name just a few – you've ensured the highest levels of visual and audio quality.

Working on films and series with global distribution requires a balance between technological innovation and cultural identity. What strategies do you employ to maintain this understanding and ensure an impact that preserves both of these aspects?

Ralph T.Y.C

Company Background

Live Tone became a subsidiary of Dexter Studios in 2017 during the production of Along with the Gods. At the time, Dexter Studios was seeking to establish itself as Asia’s leading post-production powerhouse but had not yet developed a dedicated sound division.

Live Tone’s proven expertise and track record made the partnership a natural fit, enabling Dexter to complete its full suite of post-production services.

Philosophy of Innovation

At the core of Live Tone’s philosophy is continuous innovation. Dexter Studios’ in-house R&D department focuses on developing cutting-edge audio and video technologies while maintaining an efficient production pipeline. Within this ecosystem, Live Tone plays a pivotal role. Collaboration lies at the heart of our process, ensuring that we consistently deliver results of the highest quality - results that meet and exceed the expectations of both filmmakers and audiences worldwide.

Cultural Identity as Creative Power

Unlike conventional manufacturing, what we produce is not a tangible object but an intangible cultural creation that carries meaning beyond the technical.

Every project reflects both the unique sentiments of Korea and the universal sensibilities of global storytelling.

At Live Tone, we are deeply committed to preserving Korea’s distinctive cultural identity while also embracing the language of global cinema. By blending these two dimensions, our work resonates not only with Korean audiences but also with viewers across the world. Our mission is to nurture, sustain, and share the unique sentiment of Korean culture on a universal stage.

What Is Most Korean Is Most Global

The phrase “What is most Korean is what is most global” has long served as a guiding motto in Korea. Today, it is no longer just a slogan, but a reality proven in the global market, with countless examples to show. If technological innovation determines the completeness and quality of a work, cultural identity defines its emotional resonance and charm.

Live Tone has continuously introduced and applied the latest technologies at a pace that stands shoulder to shoulder with any sound studio worldwide.

Through relentless research and experimentation, we have ensured that our technical innovation remains globally competitive, even when compared to the world’s most renowned studios. Yet while we explore and master diverse areas of technology, the way we direct, and express sound is always rooted in Live Tone’s unique identity.

Global Vision

The cultural language created in Korea now extends far beyond the borders of a single nation. It carries messages to people across countless countries and regions, moving and inspiring global audiences. We believe we are in the process of shaping another global standard. For this reason, our focus is not on how much of our cultural identity we should reveal, but on how freely we can embrace and express it. We are convinced this is the path to providing deeper inspiration to all who love culture.

5. Among South Korea's well-known and recognized directors, Kim Jee-Woon undeniably stands out for his versatile yet recognizable style.

Capable of navigating multiple genres with an original and unconventional versatility, he introduced audiences to horror, first in a tragicomic and macabre vein with The Quiet Family, and then led them into the psychological and disturbing perspective of A Tale of Two Sisters.

The Foul King serves as a diversion between the two aforementioned works; allegory reinforces the dreamlike sequences, dominating Kim's typical heterogeneous registers.

The main theme is a fierce daily struggle, which finds release and relief in a combat sport and entertainment.

Kim Jee-Woon's cinematic journey begins to take shape more strongly with films like

A Bittersweet Life, where the hierarchies and rules of the gangster world dictate the pace of events; he then offers us unbridled action and humor amidst gunfights and chases in The Good, the Bad, the Weird, a reimagined and adapted version of the Italian Spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

Kim has always admired Sergio Leone for his ability to maintain great tension despite a slow pace, for his long takes that capture the viewer's attention, and for his characters who, unlike traditional American Western heroes, each have unique and complex traits: morally ambiguous figures, far from stereotypes.

The road is defined with I Saw the Devil, where all of man's chilling brutality and inability to feel remorse are revealed uncensored, leading us to extreme and dizzying emotions.

This then solidifies with The Age of Shadows, which opens the door to a thrilling patriotic drama, a historical-political film with hypnotic spectacle: the element of double-crossing is pushed to the extreme with evocative classicism and elegance.

The science fiction and dystopian future component is fulfilled with Illang: The Wolf Brigade, where re-embracing one's humanity or choosing the pack is crucial to the outcome; a deliberate duality that bounces between mission and emotion: an adaptation of the 1999 Japanese animated film Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade and part of Mamoru Oshii's never-ending Kerberos Saga.

Completing this path is Cobweb, an open fight against censorship and a celebration of the creativity of genius; A scenic chaos that perfectly represents the embryonic stage of a project, when it's itching to come to light, not only in the director's imagination but also on film: a grueling and tormenting struggle that finds peace only in moments of maximum inspiration.

I imagine the sound design followed the same stimulating path, made up of different yet decisive emotional peaks.

You also have a commendable partnership with Kim Jee-Woon, which is precisely why I'd like to know: how have you addressed the expressive and stylistic demands of such diverse film genres and their shifts in register over the years of collaboration?

Through the art of sound, how did you help the director create his distinctive signature while moving between the natural and the artificial, between realistic environments and grotesque or surreal situations?

Ralph T.Y.C

“Finessing a Single Fader Between Reality and Exaggeration”

When I work with director Kim Jee-woon, the first thing we align on is the ratio between realism and style. Unlike Bong Joon-ho, Kim employs a distinctly his-own set of stylized devices. My approach is to build the track on the materiality and space of the real world (diegetic sound) and push exaggerated elements (non-diegetic sound) only at the emotional peak. Once we agree on that balance early, the breath, rhythm, and grain of the soundtrack flow in one direction inside the director’s sonic worldview—no matter the genre.

I’ve collaborated on most of Kim’s features and series (with the exception of The Quiet Family and The Last Stand), and I approach each project through the following steps.

Collaboration Process

Early spotting & keyword setting

At the locked-cut stage, we define the emotional spine and color of major cuts and scenes (cold/warm, dry/humid) and set a shared “realism 70: style 30” dial for guidance.

Sound-palette board

We assign signature timbres to characters, locations, and props (glass/metal/leather/wood/wind, etc.), and share that palette so Foley and design adhere to the same rules.

Designing silence

In Kim’s films, tension comes less from “more sound” and more from where and how long the silence sits. I structure a base rhythm of silence → micro-noise → rupture.

Spatial continuity

I capture impulse responses from the actual or analogous locations and apply them via convolution reverb. Only at emotional crests do I lightly exaggerate algorithmic reverb and height channels (Dolby Atmos format) to add style.

Mix goals by Style format

For theatrical mixes, I open up the low end (30–80 Hz; e.g., The Good, the Bad, the Weird / Illang: The Wolf Brigade) and the air band (10 kHz+; e.g., A Tale of Two Sisters, I Saw the Devil) to heighten weight and atmosphere.

For home/mobile (e.g., Apple TV+ Dr. Brain), dialogue intelligibility takes precedence. Dolby Atmos/7.1ch are my tool for shaping the audience’s psychological distance.

Sound by Genre and Tone

• Psychological Horror – A Tale of Two Sisters

I amplify micro-domestic sounds (floorboards, fabric, door frames) and use off-screen sound to expand imagined space. A half-beat of delayed silence after a scare deepens unease.

• Allegory/Fantasy – The Foul King

Ring action, crowd reactions, and footsteps on the ring mat become rhythmic sources.

At impact, I briefly the cheers of the audience and the low-end sound of the wrestling strike are exaggerated to create a destruction of comedy and humor.

• Noir/Organized-crime – A Bittersweet Life

Rather than sheer gun big loudness, I emphasize metallic tails and urban indoor reflections to make power feel cold; dialogue contrast stays high to convey emotional detachment.

• Western/Chase – The Good, the Bad, the Weird

Wind, hoofbeats, and sand spray serve as a tempo metronome that preserves long-take breathing. Instead of foreground bombast, I layer background rhythms, sustaining Leone-like tension through incremental environmental detail.

• Revenge Thriller – I Saw the Devil

Close-miked Foley sound (skin, fabric, metal) and wet textures sound maximize tactility. With volum mixing automation, I synchronize actor's breath with the audience’s heart rate to the scene.

• Period/Espionage – The Age of Shadows

Leather, steam, rails, and telegraph clicks form recurring motif-noises that hint at trust and betrayal. Crowds and spaces retain continuity via on-site impulse captures.

• SF/Dystopia – Illang: The Wolf Brigade

Exoskeletons, helmets, and servos are dual-layered—real machinery plus synthesized noise—to sonify the boundary between human and system. For comms, I imply inhumanity via bandwidth omission rather than heavy filtering.

• Meta/Censorship – Cobweb

I cross-cut the chaos of set sounds (slates, lighting fans, camera motors, fire) with the polish of the “finished” track to sonically stage the tug-of-war between creation and censorship.

Principles that underpin Kim Jee-Woon's signature, in My Sound Design

Presence before speech – Subtly vary each character’s personal noise (gait, clothing, breathing) so their existence is heard before they speak.

Silence as designed space – Treat silence as designed space, not absence; it unfolds for just a moment, allowing you to experience the explosion.

Timing over loudness – Favor reaction-sound timing over sheer level to create fear and humor.

Internal cuts in long takes – Even without cuts, the subtle and detailed layering/reduction of ambient sounds creates an internal cut that keeps the audience captivated.

In short, my job is to build an aural bridge that lets the director move freely between the real and the artificial, the realistic and the grotesque.

The audio dial position shifts from film to film, but by keeping rule with palette, rhythm, and space, audiences can recognize, by ear first, “this is Kim Jee-woon’s world.”

Preserving that continuity is the core of my sound-design philosophy.

6. Your work includes several notable historical, political and patriotic films—some biographical, others inspired by real-life contexts—which, in my opinion, wonderfully capture the depth of the South Korean spirit.

"There is no country without its people. Without people, there are no kings."

The Admiral: Roaring Currents still holds the record for the most-watched and highest-grossing film in South Korean cinema history, having surpassed 17 million viewers.

Thanks to this film, you won the Technical Award at the Chunsa Film Art Awards.

The most recent films, Harbin—with cinematography that I dare say is almost Caravaggio-esque—12.12: The Day, The Man Standing Next, The King's Letters, The Fortress, Man of Will, The Age of Shadows and The Throne, represent just a fraction of the rich library from the LiveTone studio: examples of refined and meticulous sound design.

In these works, every physical contact, every piece of clothing worn, every movement, breath, or word plays a crucial role in the sound design; all these elements, in turn, interact with a surrounding environment that differs in structure, conditions, and era.

When working on historical periods, especially those closely linked to real events, fidelity to reality becomes essential: contemporary sounds do not necessarily coincide with those of the past, as they reflect differences in context, culture, and daily habits. Reproducing the sounds of machinery, means of transportation, or period objects requires in-depth research, combined with a sensitivity capable of conveying authenticity and evocative power.

In this scenario, the role of the foley artist becomes crucial, recreating sound effects essential to immersing the viewer in the era depicted.

Furthermore, in films featuring military action, the number of people involved is generally high, so the sound designer's work must be equally meticulous.

Which of the visual works of this genre that you have worked on have proven most laborious and complex? Are there particular sounds that, in order to be used or recreated, required choices that transformed the work itinerary into an "impossible" undertaking?

Ralph T.Y.C

The Greatest Challenge in Sound Design for Historical Films

The most difficult part of sound design in historical films is the need to rebuild the sound library of that era from scratch. While certain sounds can still be recorded or recreated today, many have already disappeared. To revive those lost sounds, fresh ideas and thorough research are essential.Reproducing the sounds of the past with 100% accuracy is nearly impossible. Even if it were possible, films - unless they are documentaries - must always be based on cinematic reality rather than strict historical fidelity.

Film The Admiral: Roaring Currents (Myeongnyang)

• Turtle Ship Construction Scene

The film features a scene where numerous carpenters work together to build a turtle ship.

In today’s world, however, it is nearly impossible to find so many carpenters gathered in one place, simultaneously working on massive pieces of timber.

After extensive research, I discovered a traditional carpentry academy deep in the mountains of Pyeongchang, Gangwon Province.

There, students were practicing by cutting and shaping enormous wooden beams.

My team installed microphones throughout the site and recorded the sounds of cutting, hammering, and shaping wood to capture the effects and ambience needed for the shipbuilding sequence.

• Naval Battle Scene (Collision of Panokseon Ships)

Admiral Yi Sun-sin’s strategy involved ramming the Korean Panokseon ships into Japanese vessels to destroy them. To express this, I needed the sound of massive wooden ships crashing and breaking apart.I obtained an invaluable library of recordings from Rob Nokes - who had previously provided sea lion sounds for the film The Host.

At a lumber mill, enormous logs were lifted by cranes and dropped onto piles of wood, producing explosive crashing effects. These recordings became the basis for designing the powerful battle sounds in The Admiral: Roaring Currents.

• Battle Crowd Sounds (Walla Recordings)

To capture the soldiers’ shouts in battle scenes, I employed two methods:

1. On the day when the largest number of extras were gathered on set, we recorded general battle walla outdoors immediately after shooting.

2. During post-production, we brought 20–30 actors into the mixing stage to re-record specific shouts tailored to certain scenes.

These recordings were archived as a sound library and later used in designing various crowd scenes.

Film King and the Clown (Wang-ui namja)

• Samulnori and Tightrope Walking

At the time, there was no existing sound library for Korean traditional music performances such as samulnori, nor for acrobatic sounds like tightrope walking.

To address this, I directly recruited performers, including actual samulnori musicians who also appeared in the film. My team set up multichannel microphones at their practice space to record their live performances.

In addition, all sound effects for the tightrope sequences were captured through direct recording and integrated into the film’s sound design.

Film Evil Spirit: Vengeance (Gungnyeo)

• Designing the Ghost’s Voice

This period horror film required ghost sounds that were distinct from both Western and traditional Asian portrayals.I recalled a memorable scene from the French film Delicatessen, where the protagonist plays a musical saw.

Inspired by this, I located a professional saw player in Korea and brought him into the studio to perform. The recording sessions produced unique and haunting tones, enabling me to design ghost sounds that were both original and deeply rooted in Korean sensibility.

My Personal “Sound Memory Archive”

All of these projects were possible because I have been storing the sounds I’ve heard throughout my life in a personal “sound memory archive.” Rediscovering these memories, reinterpreting them, and applying them in new contexts has always been an exciting and inspiring process.This archive continues to grow and expand, and I believe it will remain a valuable treasure trove—something I can always return to and draw from for future works.

7. Your work coordination begins in pre-production, with the definition of timelines, budgets, and responsibilities for the various groups. In a process that involves highly specialized teams—from dialogue to ADR, from sound effects to Foley, all the way to the final mix—what is your method for maintaining cohesion, connection, and a collaborative spirit, while ensuring technical quality and a shared vision even under the pressure of deadlines and budget constraints? Can you outline the team "rituals" you consider essential for maintaining technical rigor and creativity throughout the workflow?

Ralph T.Y.C

External and Internal Challenges

I always strive to maintain the highest audio quality and to lead my team with continuous growth as our goal. However, in reality, there are inevitable challenges: external pressures such as budget constraints and frequent schedule adjustments, and internal issues such as training team members, adjusting plans according to external timetables, and dealing with staff turnover and restructuring.

Through many years of experience, I have learned to anticipate, prepare for, and resolve these unstable factors, developing a wide range of know-how and response strategies. Since nothing ever goes exactly as planned, I approach every new variable with a positive and proactive mindset. Yet, I do not attempt to embrace every difficulty indiscriminately. Instead, I follow my own principles, and when these principles are met, I address the situation with full commitment.

My principles

• Every request must be rational and reasonable.

• I avoid projects where my team’s efforts are consumed without meaning.

• When work has value, I prioritize its artistic significance over budget concerns.

• I distinguish whether a client treats us as true partners or merely as subcontractors.

• I never work with clients who dismiss our efforts lightly.

• A true partner is a lifelong ally, bound by loyalty and mutual support.

• Team members must be independent thinkers and decision-makers.

• The mindset of an artist takes precedence over that of a laborer.

• Every task must be approached with honesty, sincerity, and our utmost effort.

• One must establish the right professional attitude for oneself.

• Dishonest work inevitably produces dishonest results.

• A product created without soul will be recognized as lifeless.

• I never collaborate with those whose philosophy and values are fundamentally misaligned with mine.

• I refuse to work with people who see others merely as tools to be used.

• Creativity is born from 1% inspiration and 99% persistence, repetition, and trial and error.

→ Once discovered, true creativity does not disappear; it continues to grow.

Internal Management and Future Vision

To maintain the quality of our work, I have implemented a sound supervisor system.

This allows us to:

• Check whether project schedules are being properly followed,

• Regularly review and confirm the quality of sound work, and

• Engage in thorough discussions between the supervisors and mixers to refine results.

This process prevents team members from becoming trapped in excessive individualism or isolated approaches, ensuring that the overall direction and quality of the work are preserved through continuous management and feedback.

Unlike 20 years ago, LiveTone now faces new challenges due to the values and lifestyles of the younger Millennials and Gen Z of crew members. However, I do not view this as simple disruption. Instead, I see it as a natural transformation driven by a shifting industrial paradigm. I believe we are entering a critical period of transition, preparing for the next 20 years with a new working system and approach to sound production.

8. Live Tone has distinguished itself diligently in preserving audio heritage, as demonstrated by the donation of numerous materials to the Korean Film Archive, a vital cultural commitment. Today, thanks to more advanced audio technologies, how do you think domestic companies can reconcile the cultural preservation of sound with the need to archive content in order to preserve its quality over time and ensure its value on the global market?

Ralph T.Y.C - My work is never the result of my individual effort alone. It is the culmination of the dedication and artistry of directors, producers, on-set crews, post-production teams, and my own team working together. I do not view these results as temporary products to be consumed and forgotten, but as cultural legacies that should be preserved and shared with future generations of sound professionals. Through archiving, we can ensure that today’s achievements remain accessible, allowing future practitioners to understand their roots, draw fresh inspiration, and carry ideas forward - connecting the past, present, and future in meaningful ways.

While material legacies such as money or property may lose value or change over time, I firmly believe that the body of work we archive will never disappear.

On the contrary, it will grow in significance and value as time passes. However, the materials accumulated so far exist across diverse media and formats.

A critical challenge we face is to migrate them into unified, stable, and modern preservation systems and to manage them continuously.

Yet it is difficult for a private company like Live Tone to take full responsibility for this mission alone, due to limitations in both manpower and budget. This is why I believe it is essential for national cultural institutions - such as the Korean Film Archive - to take a more active role and work in close collaboration with companies like ours, ensuring that these invaluable sound legacies are properly preserved and passed on.

9. You have repeatedly emphasized that the audio experience of a film reaches its full potential only in the theater, where technologies like Dolby Atmos ensure a unique spatiality and dialogue clarity that's difficult to replicate on home theaters or OTT platforms designed for mobile viewing.

Considering this first unknown, what future do you envision for the film industry, which must balance the need for sound quality in theaters with the evolution of home viewing?

In parallel, the second unknown concerns the growing use of artificial intelligence: how do you see the impact of AI in audio post-production, and what advantages or, conversely, risks arise from this technology, also considering the growing collaboration between Live Tone and Supertone to optimize sound across different platforms and strengthen competitiveness?

Ralph T.Y.C - In a typical home environment, home entertainment cannot easily achieve standardized listening conditions unless one invests enormous sums in high-end audio systems and perfectly designed, independent home theater spaces.

As a result, the audiovisual experience at home inevitably lacks the intensity and dramatic immersion that movie theaters provide.

Today, global OTT platforms are producing films of unprecedented quantity and quality, allowing audiences to consume content more easily in domestic settings without the temporal and spatial constraints of theatergoing.

This shift has begun to disrupt the traditional viewing culture in which audiences once enjoyed a wide range of genres—from drama to action and science fiction—exclusively in cinemas.

Nevertheless, large-scale action blockbusters and other films that rely heavily on overwhelming audiovisual spectacle continue to justify the value of theatrical viewing.

In particular, premium formats such as IMAX, Dolby Cinema, ScreenX and 4DX, which cannot be replicated in the home environment, are drawing greater popularity than standard auditoriums and remain strong incentives for audiences to visit theaters.

For this reason, the film industry must secure clear differentiation from OTT services by creating and producing content that provides unique, unparalleled cinematic experiences available only in theaters. It is essential to design works that allow audiences to fully understand and agree with the question of why films must still be experienced on the big screen.

The legacy model of traditional moviegoing no longer holds the same appeal for younger generations, particularly the Millennials and Gen Z, who now constitute a primary consumer base. The industry must therefore develop strategies targeted at this audience, offering not just screenings but distinctive, memorable experiences that go beyond simple viewing.

Above all, filmmakers must never abandon the essence of cinema—its inherent aesthetics, mise-en-scène, artistry, and philosophical depth.

Preserving these elements is the very reason why theaters should continue to exist in the OTT era, and it represents the unique, irreplaceable value of cinema as an art form.

At present, the use of AI in audio post-production is still relatively limited, though it is steadily expanding. In our studio, for instance, we primarily apply AI to technical tasks such as noise reduction, removing unwanted reverb, and matching dialogue tones recorded in different acoustic environments. We have also been experimenting with AI tools that assist in creating sound effects. Some of the more advanced systems we are testing include models that can learn an actor’s voice and then generate dialogue in that actor’s tone and performance style, as well as tools capable of restoring low-quality production sound into high-fidelity audio. These applications remain focused on objective and technical areas, while legal and ethical issues - such as copyright and ongoing discussions with actors’ and voice artists’ unions - continue to limit wider adoption.

From these examples, it is clear that audio AI brings both opportunities and risks.

On the positive side, it significantly improves efficiency by automating repetitive technical processes, freeing sound professionals to focus on creative storytelling and artistic expression. It also provides scalability across multiple platforms - cinema, OTT, mobile, and gaming - and reduces costs, which can be particularly beneficial for smaller studios.